Four VSC benchmark system

Reviewers: Mathilde Bongrain (CRESYM)

Use case features

This 100% power electronics small test system relies on Voltage Source Converters (VSC) operating in grid following mode. It aims at showing the limitations of the phasor approximation. Hence, there is an EMT and an RMS version of this system.

The system was designed to offer the following features:

- being small enough for its stability margins to be easily assessed

- involving several VSCs electrically rather close to each other (to contemplate possible interactions)

- being connected to an external grid of adjustable strength in terms of short-circuit power

- relying on generic models

- being freely available.

References

This benchmark was originally proposed by Prof. Thierry Van Cutsem (formerly with University of Liège, Belgium, acting as consultant for CRESYM). The VSC dynamic model was developed and validated by the team of Prof. Xavier Guillaud (Ecole Centrale de Lille, France). As part of the BiGER project (CRESYM), this test system has been implemented in Dynawo and EMTP.

Network description

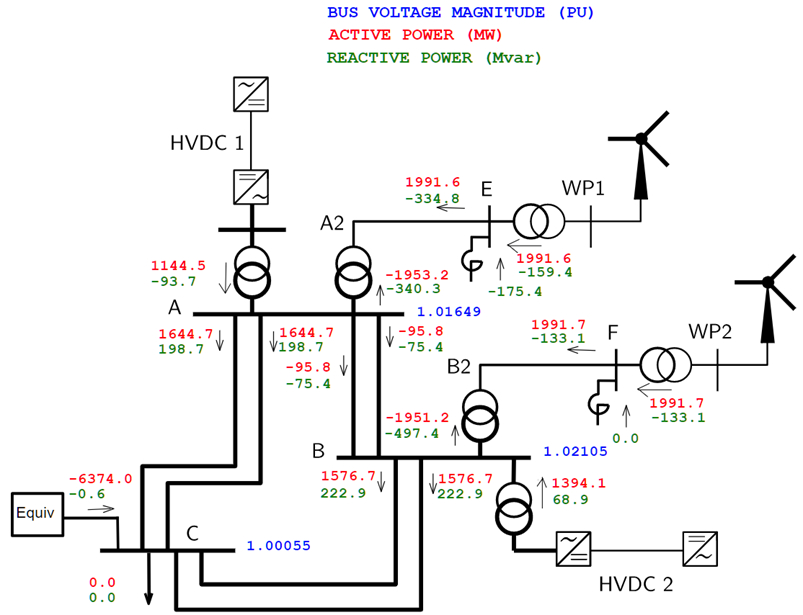

The one-line diagram is shown in the following figure (Fig.1):

Fig.1. one line diagram

The system hosts two wind parks (WP1 and WP2) and the terminal converters of two HVDC links (HVDC1 and HVDC2). The remote converter of each HVDC link is not modelled, the DC voltage being assumed constant. WP1 and WP2 are aggregated equivalents of a large number of generators. The connection transformers of all four VSCs are represented explicitly.

The connection to an external system is considered through the Thévenin equivalent attached to bus C. Since the Thévenin voltage source forces the system frequency to return to its nominal value in steady state, this 100% power-electronics based system is clearly not meant to address frequency issues.

The 400-kV part of the transmission grid is meshed, allowing to simulate the outage of one or two circuits without disconnection from the external system. The line lenghts are given in Fig. 1. Each wind park is radially connected to the grid through six 225-kV cables and six transformers in parallel to cope with the maximum production of each park. The cables are 50 km long and correspond to the AC connection of an offshore wind farm. The shunt reactors at buses E and F aim at absorbing the excess reactive power produced by the cables. The line, cable, transformer and VSC parameters are given in Table 1, 2 and 3, respectively.

| R (\(\Omega/km\)) | X (\(\Omega/km\)) | \(\omega *\frac{C}{2}\) (\(\nu S/km\)) | Snom (\(MVA\)) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 400-kV* | 0.016 | 0.320 | 1.5 | 1300 |

| 225-kV** | 0.0084 | 0.017 | 180.0 | 2400 |

Table 1: line and cable data

* pertain to each circuit ** pertain to 6 cables in parallel

| Transformer | Nominal Voltage (V) | R (pu) | X (pu) | \(n\) | Snom (MVA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1-A | 320/400 | 0.005 | 0.15 | 1.02 | 1200 |

| B1-A | 320/400 | 0.005 | 0.15 | 1.04 | 1700 |

| A2-A | 225/400 | 0.005 | 0.15 | 1.02 | 2400 |

| B2-B | 225/400 | 0.005 | 0.15 | 1.05 | 2400 |

| WP1-E* | 66/225 | 0.005 | 12.0 | 1.05 | 2400 |

| WP2-F* | 66/225 | 0.005 | 12.0 | 1.04 | 2400 |

Table 2: Transformer data

| Converter | Snom (MVA) | Pnom (MVA) |

|---|---|---|

| WP1 | 2400 | 2300 |

| WP2 | 2400 | 2300 |

| HVDC1 | 1200 | 1150 |

| HVDC2 | 1700 | 1630 |

Table 3: Converter data

Dynamic models

A single dynamic model is used for all four converters (though with a control variant for WP1 with respect to the other VSCs).

Operating points

Two operating points were considered in the simulations, as detailed in Table 4.

| operating point # | power (MW) injected by | power (MW) into equiv. | load (MW) at bus C | power (Mvar) of shunt reactors | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WP1 | WP2 | HVDC1 | HVDC2 | ||||

| 1 | 2000 | 2000 | 1150 | 1400 | 6374 | 0 | 160 |

| 2 | 2000 | 2000 | -1120 | -1600 | 0 | 1169 | 500 |

Table 4: Operating points

The first operating conditions result in a heavily loaded network, both wind parks and both HVDC links injecting active power into the grid. Nevertheless, the system is N-1 secure with respect to the outage of any 400-kV circuit. No load is present. Hence, the whole production (minus the network losses) is exported to the external system represented by the Thévenin equivalent at bus C, whose short-circuit power has been set to 10 GVA. The operating point is shown in detail in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2: Operating point #1

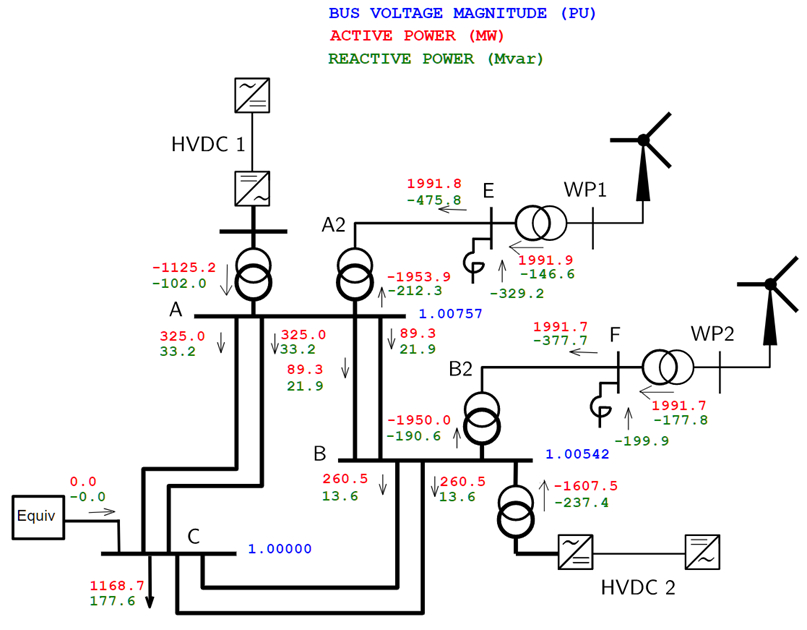

In the second operating point, the wind parks inject the same power, a large fraction of which is evacuated by the HDVC links. This results in a lightly loaded network with larger shunt reactors connected. At this operating point, stability is assessed in terms of minimal short-circuit power of the external system. The corresponding Thévenin reactance is varied. The net power injection of the VSCs (minus the network losses) is taken by the load at bus C, which results in no power flowing into the Th´evenin equivalent. Hence, the initial state remains unchanged while the reactance is varied and there is no risk of reaching the (static) loadability limit of the equivalent (for large values of its reactance). The operating point is shown in detail in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3: Operating point #2

Scenarios and example of simulation results

Scenario #1

Scenario # 1 relates to Operating point #1. The event is a solid three-phase fault on one of the two circuits of line A-C, next to bus A. The fault is cleared after 150 ms by opening the line, which remains open. The purpose of the simulation is to test the response to a large disturbance leading to current limitation in the VSCs.

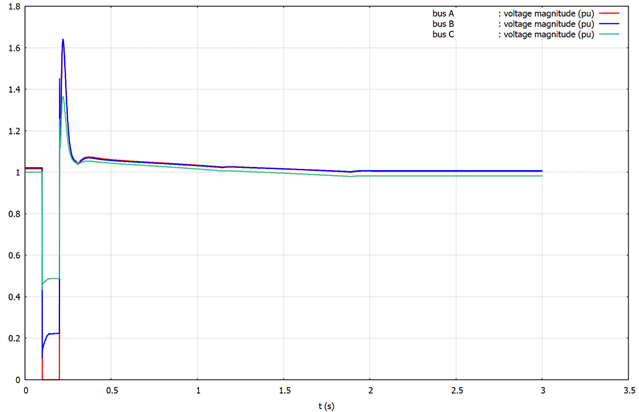

The voltage evolutions are given in Fig. 4. During the fault, the voltage at bus A drops to zero, due to the proximity to the fault. The residual voltages at buses B and C are easily explained by their electrical distances from bus A. Voltages quickly recover after fault clearing but they undergo a peak, due to the large injection of reactive power (large value of \(i_q\) component of current) during the fault with the aim of supporting voltages. It is of interest to check the value of that peak with EMT simulation.

Fig. 4: Operating point #1: voltages

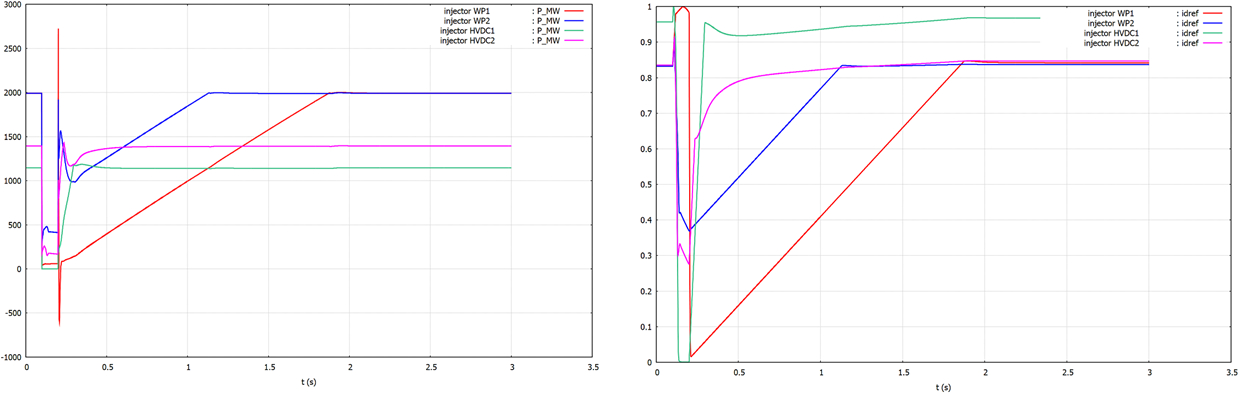

The evolution of the VSC active powers is shown in Fig. 5 (left part). During the fault, the active power of HVDC1 drops to zero owing to the zero voltage at bus A. The other three VSCs undergo a severe drop of their active power, owing to the priority given to reactive power. After fault clearing, the active powers regain their pre-disturbance values but with the imposed maximum rate of recovery. The latter is faster for the two HVDC links than for the two wind parks. The right part of the figure shows the corresponding setpoint values of the id components. These setpoints are the input the fact current control loops.

Fig. 5: Operating point #1: : active powers and id current setpoints

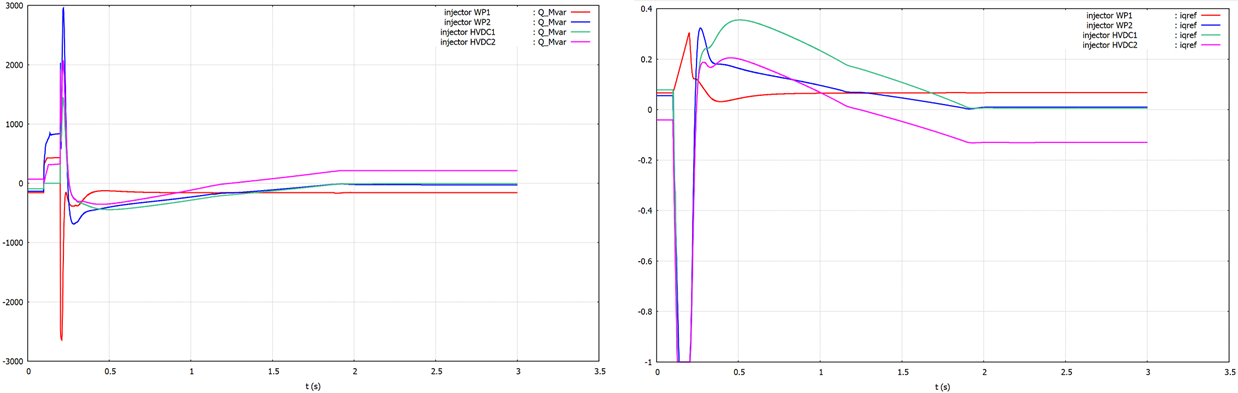

The evolution of the reactive powers is shown in the left part of Fig. 6 while the setpoint values of the iq components are shown in the right part. During the fault, all VSCs have their reactive power increased but their \(i_q\) components evolve differently:

- WP2, HVDC1 and HVDC2 control their voltages (on the converter side of the connection transformer). The severe voltage drop caused by the fault is counteracted by a quick decrease of \(i_q\), which corresponds to maximum injection of reactive power. iq hits the -1 limit, which corresponds to the whole current being taken by the iq component (\(i_d = 0\)), in accordance with the reactive power priority;

- WP1 is under reactive power control. During the fault, \(i_q\) increases in order to counteract the reactive power increase, before regaining its pre-disturbance value.

Fig.6 Scenario #1 : reactive powers and iq current setpoints

Scenario #2

Scenario #2 relies on Operating point #2. The event is the opening of one circuit of the line between buses A and B. This 400-kV circuit carrying only 90 MW, the disturbance can be considered small; the purpose of the simulation is to test the small-disturbance stability of the resulting operating point.

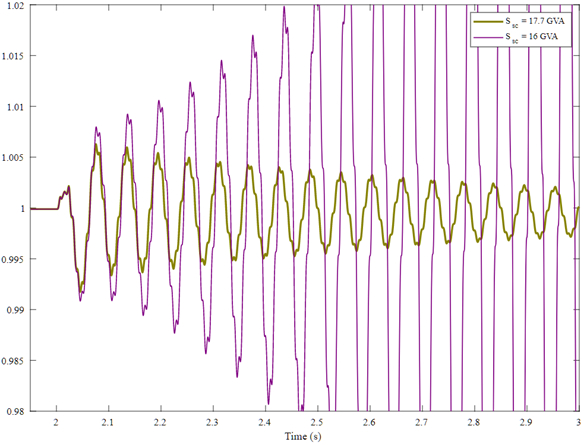

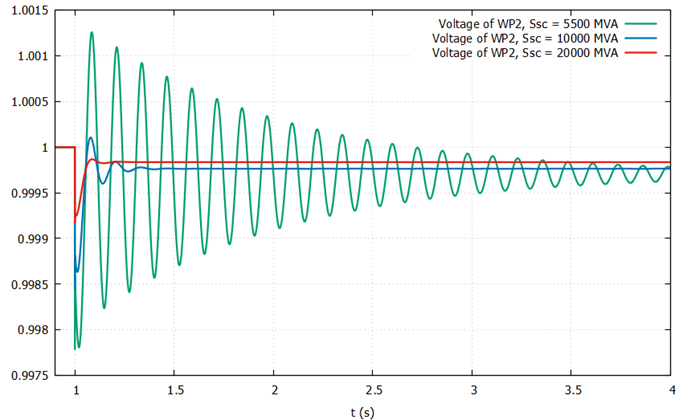

In order to find the stability limit of the system, the short-circuit power of the external system (connected to bus C) is progressively decreased, until the response to the disturbance becomes unacceptable, owing to undamped oscillations.

The limit value of the short-circuit power obtained with respectively EMT and phasor simulations have been compared. The marginal cases are shown in Fig. 7 for the EMT simulation and Fig. 8 for the phasor-mode simulation. It can be seen that in EMT simulations the system becomes unstable for a short-circuit power around 16 GVA, while in phasor-mode simulations it becomes unacceptable at 5.5 GVA. There is thus a very significant difference. This scenario is very appropriate for future analysis in the BiGER (CRESYM) project.

Fig.7 Scenario #2 : EMT simulations in marginal cases

Fig.8 Scenario #2: Phasor-mode simulation in marginal cases

Open source implementations

Some open source implementations of this use case are available in the following software solutions:

| Software | URL | Language | Open-Source License | Last consulted date | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynawo | Link | modelica | MPL v2.0 | 17/05/2024 | - |

| STEPSS | Link | own modelling language | models in open source | 17/05/2024 | - |

| EMTP-RV | to be completed | .ecf | MPL v2.0 | - | |

| SimPowerSystem | to be completed | Matlab | to be completed | - |